Published

09/22/2025, 18:00It’s no secret that China has long become one of the hubs of technological advancement. Some skeptics might argue that technological marvels can only be seen in major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, or Hong Kong. However, their misconception needs to be dispelled. Over the course of a week, I visited three cities in Xinjiang and saw firsthand how goods are produced, noting several distinctive features.

It is worth noting that the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is largely located within the Taklamakan Desert. Such a geographical location naturally influences city life. However, despite this, all three cities I visited were green and comfortable to live in. This is particularly remarkable given that water scarcity in the region is as pressing an issue as it is for residents of Central Asia.

In 2024, Xinjiang’s economy recorded one of the highest growth rates in China, with regional GDP rising by 6.1% and surpassing 2 trillion yuan ($281 billion) for the first time. Industrial output grew by 8%, fixed-asset investment increased by 6.9%, retail sales of consumer goods rose by 2%, foreign trade jumped by 21.8%, and budget revenues grew by 10.5%. These results were achieved through a well-planned approach to economic development.

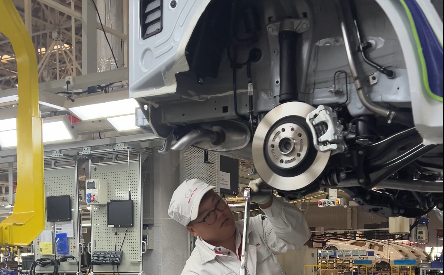

The first enterprise our group visited was the Xinjiang branch of the GAC automobile plant, opened in 2016. Today, it operates as a high-tech assembly line, producing cars from pre-fabricated components. Across the region, there are 15 first-class and 27 second-class dealerships, while at the plant itself, robots play a key role: mechanical arms hold the car bodies and engines, automation systems monitor precision, and quality control is integrated at every stage. The result is minimized errors and products that meet the company’s high standards.

By the way, training for new employees takes place directly at the plant. To test the readiness of recruits, a simple simulator resembling a children’s puzzle is placed in the training room. However, despite its apparent simplicity, I was unable to complete the task without mistakes. The objective is to move a lever without touching the walls of the maze, while various sounds are triggered to distract you. It is worth noting, though, that none of the other group members were able to complete the task perfectly either.

The final assembled product can be tested right in the showroom. The cars, beautiful as if taken straight from a picture, are equipped with the latest technology. But, to be honest, the most impressive feature for me was the built-in massager. You can immediately imagine sitting in a brand-new car after a long day at work, gliding silently down the road (by the way, in China, even next to a busy highway, you won’t hear the roar of the engine — author’s note), while it simultaneously massages your back.

It is worth noting that Chinese cities make an effort to plant as many trees as possible, and production sites are no exception. Preference is given not to ornamental trees, which would struggle to survive in the region, but to species that adapt well to the local conditions. These can include common elm trees as well as fruit trees. Such diversity helps create a comfortable environment. For example, the assembly plant has a large number of apple trees, and, as a kind gesture, we were treated to some of the fruit at the end of our visit.

The plant primarily operates on a made-to-order basis, which allows for optimized production and cost control. In general, this approach is applied at almost all enterprises, whether it’s a rice-milling factory or a solar panel manufacturer. The technological efficiency of these facilities ensures uninterrupted production, while the volume of orders remains optimal, so workers retain their jobs and receive their salaries. According to statistics, over the past year, urban residents in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region became 5.5% wealthier, while rural residents saw an 8.2% increase in income.

A particularly impressive experience for me, as a woman, was visiting Tianshan Wool Tex — one of the top 10 textile enterprises in China (female readers will understand — author’s note). We didn’t get to see the production process itself, but even the showroom leaves an unforgettable impression. The company, with a registered capital of 467 million yuan (65.6 million USD), had assets of 908 million yuan (127.6 million USD) by the end of 2024 and generated an annual revenue of 486 million yuan (68.3 million USD). Its annual capacity includes processing 300 tons of cashmere, dyeing it, producing yarn, and manufacturing 600,000 cashmere and knit sweaters. The factory is equipped with machinery from Germany, Italy, and Japan. To the touch, these products are incredibly lightweight, soft, and pleasant—something every fashion enthusiast would want to add to her wardrobe—but the pleasure comes at a price. A single sweater costs 2,000 yuan, which is over 20,000 KGS. The company operates actively both within China and internationally, exporting its products abroad. Interestingly, the trade war with the U.S. had virtually no impact on their profits; according to the company’s CEO, sales dropped by only 1%.

The equipment for such factories is manufactured not far away, in Urumqi. We visited the Saurer plant and saw firsthand that the company truly lives up to its reputation as a leading global player in fiber and yarn processing. Here, not only are equipment and components assembled, but software is also integrated, and machines for tire cord, carpet backing, staple fiber, fiberglass, and technical yarns demonstrate how technology helps clients respond quickly to market changes. The cost of building a single textile factory of this type is approximately 70 billion yuan (1 billion USD). This investment covers the construction of the facility, equipping it with full-cycle machinery, and training the workforce. Even so, it seems that such a textile factory would be prohibitively expensive for our market, not to mention that its production volumes are quite substantial.

The high technological level of the equipment allows companies in general to operate without hired labor, as almost everything can be done by machines today. However, government policy inevitably impacts private businesses, and it is the state’s responsibility to provide people with jobs and resources. As a result, it is often observed that certain parts of production are deliberately left non-automated to maintain employment. For example, at a milk processing plant, the sorting stage of production is entirely handled by workers.

In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, a technological approach to agricultural production is evident not only through automation and modern machinery but also through scientific work with the soil and crop varieties. The region is located in a desert and saline-alkaline zone, where traditional farming methods are largely ineffective, so agriculture here requires a specialized approach. In Kashgar, on the fields of Paha Takeri, a team from Shenzhen managed to transform almost barren land into productive rice plantations by introducing salt-tolerant “sea rice” varieties adapted to extreme conditions. Scientists carefully selected crop varieties, monitored soil composition and acidity, and optimized irrigation and crop care, which not only significantly increased yields but also restored the region’s ecology: soil salinity dropped from over 20% to approximately 1%, the pH level returned to normal, and the fields became populated with birds and frogs once again. This example demonstrates that in Xinjiang, technology in agriculture is not just about machines, but a thoughtful combination of science, innovation, and sustainable land management.

However, all these industrial achievements cannot be fully realized without proper logistics. Urumqi hosts a crucial strategic logistics hub, as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region has the longest land border in China, providing access to eight countries: Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. According to China Railway Urumqi Group, by September 1, the port in Xinjiang had handled over 5,000 freight train trips along the China–Europe route through Central Asia. Currently, a pre-declaration system has been implemented, allowing trains to depart the port in just 20 minutes. The port now serves 125 routes across 21 countries, transporting more than 200 types of cargo. In the future, this land port will become a key route for freight trains traveling along the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan corridor.

Chinese entrepreneurs are also eagerly anticipating the construction of this route, as it creates excellent opportunities for all countries involved in the project. According to Chinese experts, building the railway, along with the modernization of the Bedel border checkpoint, will strengthen cooperation between our countries, even though trade turnover between Kyrgyzstan and China is already showing strong growth.

Experience from industrial projects in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region shows that technological advancement is not just about automation and cutting-edge equipment, but a comprehensive approach. It combines science, innovation, attention to people, and careful management of natural resources. The Chinese example teaches that success is possible only with a well-thought-out strategy, effective management, government support, and the ability to adapt to extreme conditions. This is how barren lands are transformed into fertile fields and factory floors into high-tech assembly lines. The ultimate lesson for any business or government is simple: innovations and technology work best when accompanied by systemic thinking, care for people, and sustainable development.